With famine already preying on some of Gaza’s 2.3 million people and little sign of a breakthrough in negotiations between Israel and Hamas, world governments and humanitarian groups have focused on getting more aid into the enclave.

The supplies are available, aid groups say. But roadblocks and other difficulties slow their delivery at nearly every turn. Airdrops have killed people waiting for life-sustaining supplies, trucks have been held up or turned away at the only two entry points, and people have been killed by Israeli gunfire or in stampedes — with conflicting versions of what happened following each time — at distribution points.

The situation led the top United Nations court on Thursday to order Israel to open more land crossings into Gaza.

Inside Gaza, the central problem remains: how to deliver humanitarian aid to everywhere it is needed.

What’s the situation in Gaza?

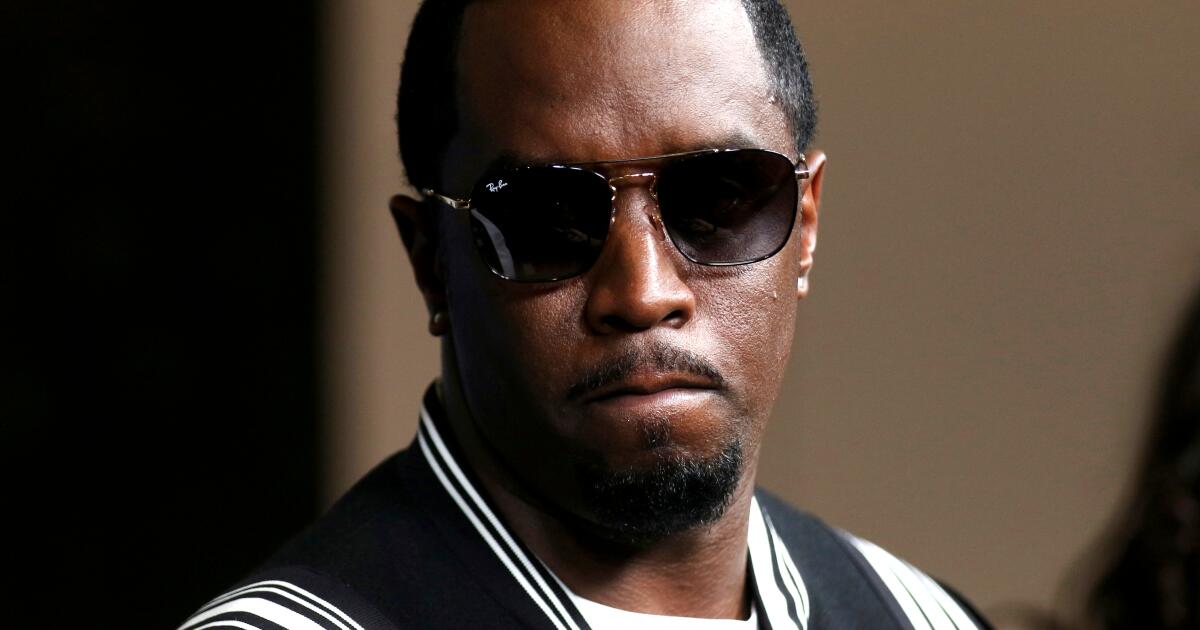

Humanitarian aid for the population of Gaza launched from a Spanish army aircraft in Gaza.

(Sipa via Associated Press)

More than five months into the war in Gaza, water, food, medicines, fuel and nearly every other essential are in short supply.

Before the war, the enclave was long subject to a blockade from Israel and Egypt, but some 500 trucks, including commercial goods and aid, would enter Gaza every day.

After the Hamas attack on Israel that killed more than 1,160 people and saw around 250 taken hostage, the bombardment of Gaza began and Israel sealed the border. The number of trucks carrying aid into Gaza dropped to under 100 per day, with most commercial goods blocked.

After international outcries, the number of trucks entering has crept up, but it is still less than a third of what came in before the war. Aid drops and fledgling attempts at maritime corridors are nowhere near covering the shortfall.

The result, according to a global initiative that tracks food insecurity, is “imminent” famine for parts of Gaza. The Integrated Food Security Phase Classification, or IPC, said in a report this month that all of Gaza’s 2.3 million people face high levels of acute food insecurity.

“The situation in Gaza is catastrophic,” said the report. “Famine is projected and imminent in the northern governates and there is a risk of Famine across the rest of the Gaza Strip.”

The famine warnings come as more than 32,600 people have already been killed in Israel’s bombing and ground war against Hamas, according to the local health ministry. And 1.7 million of the territory’s residents, half of them children, are displaced, according to UNICEF.

Israel has said reports of hunger in Gaza are exaggerations.

“As much as we know, by our analysis, there is no starvation in Gaza,” Col. Moshe Tetro, the head of the Coordination and Liaison Administration for Gaza, told reporters at a crossing point recently “There is sufficient amount of food entering Gaza every day.”

In northern Gaza, the IPC report noted, people have been scavenging from destroyed buildings and eating animal feed, but even those resources are running out. Much of the agricultural land is damaged, along with the infrastructure required to cultivate crops.

More than 210,000 of the people in the north, including Gaza City — where needs are at their most dire — already facing famine or catastrophic levels of food insecurity, the report said. By mid-July, the report said, 1.1 million people could be facing “catastrophic” lack of food. “All evidence points towards a major acceleration of death and malnutrition.”

The IPC defines famine as at least 20% of a population affected, 30% of children acutely malnourished, and two people for every 10,000 inhabitants dying of starvation or disease from malnutrition.

Why isn’t the aid coming in?

Humanitarian organizations and governments characterize Israel’s inspection procedures for trucks as convoluted, time-intensive and often seemingly arbitrary. Shipments with lifesaving goods or equipment can be delayed for weeks or rejected with no explanation.

The U.N.’s Population Fund, which has been sending supplies into Gaza to help the roughly 180 women giving birth every day and the estimated 1 million women and girls of menstrual age, had a recent delivery rejected despite the same goods going through in the past.

“At the point of inspection, the U.N. isn’t allowed to be there. So we don’t get any reason,” said Dominic Allen, the Population Fund’s representative for the Palestinian territories.

“It was puzzling to find flashlights to be rejected, to help a midwife deliver her services at night.”

Israel says it is sufficiently facilitating humanitarian deliveries. Officials have blamed delays on aid groups or on Hamas stealing supplies.

Shimon Freedman, spokesman for the Israeli agency Coordination of Government Activities in the Territories, said, “Israel places no limit on the amount of aid that can enter the Gaza Strip.” He said Israel is inspecting more humanitarian aid than international organizations on the ground can distribute, which humanitarian groups have disputed.

What happens when trucks do enter?

Egyptian trucks carrying humanitarian aid bound for the Gaza Strip queue outside the Rafah border crossing on the Egyptian side.

(Khaled Desouki / AFP / Getty Images)

With only two entry points, both in the south, trucks have to traverse miles of rubble-filled landscape.

“I used to go every month and I didn’t recognize it,” Allen said after a recent visit. “I went past roads and places I knew, but they’re destroyed. There’s no semblance of a tarmac.”

The problem is compounded because aid groups, especially the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East, known as UNRWA, have had their movements restricted by Israel and their facilities and staff hit in the fighting.

UNRWA has long been the backbone of the humanitarian response in Gaza. In January, Israel accused 12 UNRWA workers of involvement in the Oct. 7 cross-border attack. Spokesperson Juliette Touma has said the “very serious” allegations involve “12 staff out of 30,000” and that those workers were fired and the allegations are being investigated.

Two million people depend on UNRWA staff and assistance, she has said, with more than a million people living in the agency’s shelters.

“We don’t use security. Our staff are from the local community, and people know and trust UNRWA,” she said, adding that UNRWA uses police escorts only for the first part of the journey from the Kerem Shalom crossing, where the Gaza Strip, Israel and Egypt meet, to UNRWA’s headquarters less than a mile away.

But the issue, she said, has been failures in deconfliction communications with Israel: Since Oct. 7,171 agency workers have been killed in Israeli bombardment, an average of one a day, the agency says, and more than 160 of its facilities have been struck, including warehouses and distribution centers, Touma said.

UNRWA and other aid groups are also being blocked or slowed from helping the people remaining in the north of Gaza, aid workers say. The last time a UNRWA convoy made it there was at the end of January, Touma said.

UNRWA head Philippe Lazzarini said this week in a post on X that Israel told the agency its convoys would no longer be allowed to travel into the north of the Gaza Strip.

“This is outrageous & makes it intentional to obstruct lifesaving assistance during a man made famine,” Lazzarini wrote. “These restrictions must be lifted.”

International frustration grows with Israel

A view of a family’s building damaged in an Israeli attack at Maghazi refugee camp in Deir al Balah, Gaza.

(Ashraf Amra / Getty Images)

Global and Western leaders have grown increasingly exasperated with Israel, accusing it of using starvation as a weapon of war.

“This is a humanitarian crisis which is not a natural disaster. It is not a flood. It is not an earthquake. It is man-made,” the European Union’s foreign policy chief, Josep Borrell, said at the United Nations this month.

“And when we look for alternative ways of providing support — by sea or by air — we have to remind that we have to do it because the natural way of providing support through roads is being closed, artificially closed.”

On Thursday the International Court of Justice said “famine is setting in” and ordered Israel to ensure “the unhindered provision at scale by all concerned of urgently needed basic services and humanitarian assistance” in Gaza. The court issued the measures in South Africa’s case accusing Israel of acts of genocide, which Israel has denied.

Israel accused South Africa of trying to undermine Israel’s right to defend its citizens. But Israeli foreign affairs spokesman Lior Haiat said in a post on X that Israel was looking to expand “efforts to increase the scale, and means of access for such aid despite the operational challenges on the ground and Hamas’s active and abhorrent efforts to commandeer, hoard, and steal aid.”

Chaos amid desperation

The arrival of aid can spur chaos. On Monday, 12 people drowned after trying to retrieve parcels that were dropped into the sea, and six others died in the stampede to get to the supplies. Hamas demanded an end to the airlift, saying it posed a danger to the lives of Palestinians, and called for “the immediate and rapid opening of land crossings.”

Last month, more than 100 people were killed and many more wounded as Palestinians rushed to pull food off aid trucks in Gaza City. Witnesses said Israeli troops fired on the crowd and hospitals reported treating scores of gunshot victims. Israel said that many of the dead had been trampled and that its soldiers fired only when they felt endangered by the crowd.

This month, more deaths have followed at distribution points, with accounts from Israel differing from those of Hamas, health officials and witnesses.

As Israel tries to defeat Hamas, which does not recognize Israel’s right to exist, most officials affiliated with the militant group that has ruled Gaza since 2007 have gone into hiding.

With Gaza’s governing authority receding, starving Palestinians have ransacked trucks, and aid shipments have been commandeered by armed gangs that have emerged amid the security vacuum.

In an effort to contain the bedlam, Gaza’s municipal police force (which falls under Hamas’ control but has no connection to the group’s military wing) took on the job of securing aid convoys’ passage through the strip.

Aid groups have also relied on neighborhood committees — organized around influential clans — to help organize deliveries.

But the police and clan groups have also come under attack, with a police chief and two top police officials recently killed. They were all involved in securing aid centers and coordinating truck deliveries, Hamas said.

Israeli officials contend that the police are a part of Hamas and therefore a military target.

In a statement, the Government Media Office in Gaza said Israel’s targeting of figures involved with aid aims “to perpetuate the policy of starvation and deepen famine on a broader scale” and to “spread chaos.” Israel has repeatedly denied targeting aid convoys and distribution points, blaming the violence on armed Palestinians, looters and Hamas members.

Meanwhile, community initiatives seem hopelessly overwhelmed. Neighborhood aid coordinators, who normally deal with 5,000 to 10,000 people, say they have seen the number of those needing aid more than quadruple.

Because aid deliveries are so chaotic, large swaths of people go without any assistance, or risk going near Israeli army positions, where they could be killed, said Abu Mohammad Badwan, a 64-year-old from Gaza City trying to get some flour and canned goods for his family.

“Whenever people see the trucks, they just rush at it. Young guys, they go in groups of 10 and 20, and then the Israelis shoot at them,” Badwan said. He gave his nickname for reasons of safety.

For the one or two days when the assistance was organized by the police and clansmen, everyone got their share, Badwan said. But since the Israeli strikes on the police, the chaos had returned.

He mentioned recent incidents of people being shot at the Kuwaiti roundabout, which pushed Hamas to urge people to stay away from the area. Parcels dropped by air, meanwhile, end up in border areas near the Israeli army or in the sea, or lead to people fighting over them.

Even those people picking mallow — a leaf which grows in empty lots and agricultural land — or other plants to eat are in danger, he said, because of proximity to the Israelis.

“People risk all this for their kids, their sisters, their mothers,” he said.

“They sacrifice themselves for a bag of flour.”