To say Ryan Garcia has had a bad year is an understatement.

The Chicago White Sox had a bad year. For Garcia, things have risen to a whole other level of self-destruction.

The boxer entered 2024 with one loss in 25 professional fights. He was young, handsome, talented and charismatic. In a struggling sport that is all about brashness and self-promotion, Garcia seemed a savior.

Then he knocked himself out with a spectacular series of self-inflicted body blows that has sent his career to the canvas.

In January, he filed for divorce from his wife, Andrea Celina, and in April he gave up a chance to win the WBC super lightweight title when he failed to make the 140-pound weight limit for his fight with Devin Haney.

The fight went on anyway and Garcia won a majority decision, only to forfeit the upset victory — and incur $1.8 million in fines — when he tested positive for a performance-enhancing drug. That also earned him a year’s suspension.

Garcia strongly denied he knowingly took banned substances, but his troubles were only beginning.

In June he was arrested for causing thousands of dollars in damage at a tony Beverly Hills hotel; the case was dismissed last month when Garcia, who has no criminal record, paid $15,000 in restitution.

However in July his-then estranged wife — the two are currently attempting to reconcile — posted video and photos to Instagram allegedly showing the damage Garcia caused when he broke into their home. That month he was also expelled from the World Boxing Council over slurs against Blacks and Muslims he made on social media, comments for which he quickly apologized. Despite the apology, three weeks later he doubled down on X, the platform formerly known as Twitter, writing in a profane tirade that he hoped members of the LGBTQ+ community would “rot in hell.”

Lastly, in September, Haney filed a lawsuit in New York charging Garcia with battery, fraud and breach of contract over the April fight. And the boxer’s terrible, horrible, no good, very bad year isn’t over yet since 2024 still has more than six weeks to go.

The question now is can Garcia, who is training for a possible New Year Eve exhibition against a mixed martial artist in Japan and a January appearance at a festival in Dubai, climb off the canvas and save his career?Fighters may be trained to get up when they’ve been knocked down, but first they have to know they’re being counted out. And Garcia has yet to admit that.

So as he squirmed uncomfortably on a small sofa at his lawyer’s house while the rap sheet was read back to him, he also brushed aside the growing list of controversies surrounding him the way he might deflect a left hook. In his telling, he’s the victim, not the perpetrator of much of what has befallen him.

“I did make maybe one or two mistakes, for sure,” he said. “But most of it was definitely just a year of people trying to knock me down. It was just a lot of little things that I had to persevere and I had to get through.”

He also cautioned against counting him out just yet.

“It’s far from over,” he said of a once-brilliant career that has stalled. “It’s just starting. We’re heading in the right direction.”

Outside the ring and away from his social media accounts, Garcia can be funny and extremely likable. He laughs often, smiles even more frequently and is handsome in a way that makes casting agents swoon. So it wasn’t surprising to learn he’s been handed multiple scripts and is considering acting as he sits out his suspension.

But any detour, he promises, would just be temporary.

“I feel like I’m just too good at my sport to leave yet,” said Garcia, whose unshakable confidence — some would call it a cocky arrogance — is his real superpower.

“My heart’s in boxing,” he said. “It’s all I’ve ever done.”

Garcia grew up with a brother and three sisters in the Mojave Desert, where there are almost as many cacti as there are people and where the temperatures drop below freezing in the winter, then soar into the triple digits for most of the summer.

It’s also where Garcia fell in love with boxing before he had finished the second grade.

His father, Henry, a former professional fighter, was forced to give up the sport when he started a family. The sport, however, never left him. So when Ryan and his younger brother, Sean, a southpaw who has lost once in nine pro bouts, became curious about boxing, Henry stepped up to coach them.

Henry Garcia and his wife, Lisa, both became boxing officials after Ryan, then 7, embarked on a 10-year amateur career that would see him fight more than 200 times, capturing 15 national titles. But none of it was easy. The Garcias often slept in their car, they said, as they drove from event to event, overpaying the heavy dues required to advance in a sport that rewards the ability to both endure pain and to dish it out.

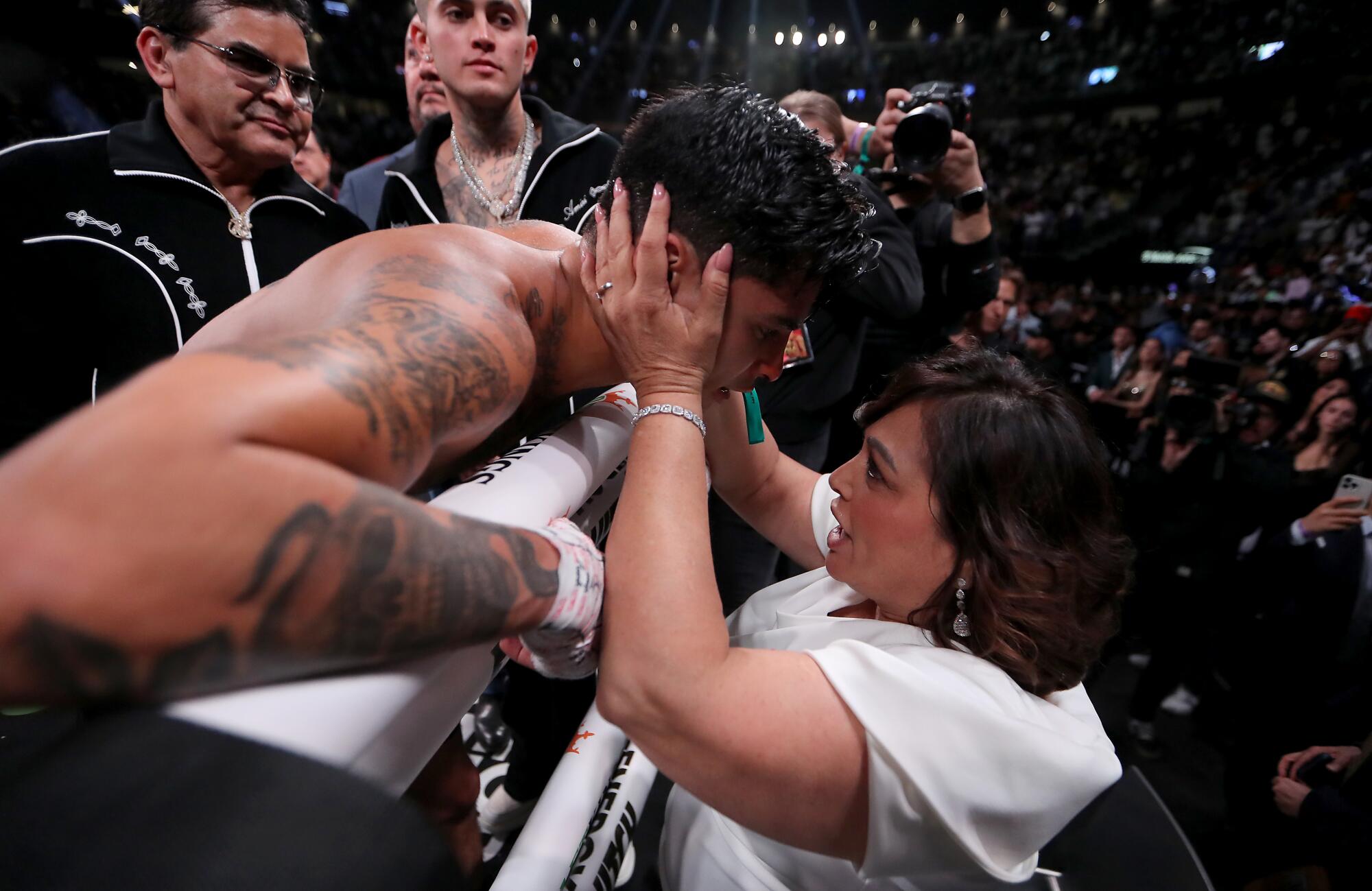

Ryan Garcia is comforted by his mother, Lisa, and his father, Henry, left, after losing by TKO to Gervonta Davis at T-Mobile Arena in Las Vegas in April 2023.

(Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times)

“He came up the hard way. You’re fighting at local bars in TJ, that’s not the easy way.”

— Manny Robles, boxing trainer

“He’s always been special. Even as an amateur fighter he was special,” said second-generation trainer Manny Robles, who has known Garcia since those amateur days. “You could tell this kid was going to excel.”

And for Garcia, making good on that promise was the only way to reward his parents’ sacrifice.

“We have had a long journey up, just kind of a lower-class family that had a big dream. They did whatever they could to take me [to] the tournaments,” said Garcia, who trades on his family’s Mexican roots, frequently carrying the tri-color flag into the ring with him although he and his parents were born in the U.S. and he speaks no Spanish.

Garcia dropped out of high school to turn pro at 17, beating Mexican lightweight Edgar Meza in his debut, which was held in a bar in Tijuana. Meza never fought again but Garcia won five bouts over the next four months — mostly fighting on small cards in pool halls and nightclubs, the kind of dark, sad, smoke-filling rooms where careers typically go to die, not to be born.

“He came up the hard way,” Robles said. “You’re fighting at local bars in TJ, that’s not the easy way.”

But despite the humble surroundings those early fights drew the attention of Oscar De La Hoya’s Golden Boy Promotions, which signed him to a contract in the fall of 2016. Suddenly he had a chance to reward his parents not just with trophies, but with money as well.

“It was a lot of pressure as a young kid,” said Garcia, whose net worth has been estimated at nearly $50 million. “You just grow and mature faster than other kids. You have different responsibilities. You feel like, ‘Oh, man, I better win this fight. They need me.’

“It was hard to see how much pressure it was during the moment. But later on it was like, ‘Dang, I actually had a lot on my plate’.”

Soon Garcia was working with Eddy Reynoso, Canelo Álvarez’s trainer, and fighting the co-main event on a card headed by Álvarez at the MGM Grand in Las Vegas.

He needed 98 seconds to win that fight, claiming the WBC silver lightweight title. But the storm clouds were already gathering.

In January 2021, in a fight delayed by COVID-19, Olympic gold medalist Luke Campbell sent Garcia to the canvas for the first time. Garcia got up to win on a seventh-round technical knockout, claiming the WBC interim lightweight title he was to defend against Javier Fortuna in a fight that would set up a title unification bout with Haney.

The Fortuna fight never happened, however, with Garcia withdrawing 11 days after the contract was signed “to manage my health and wellbeing [sic],” the boxer wrote on Instagram.

In the 46 months since beating Campbell, Garcia was suspended or arrested outside the ring as often as he won inside it as rumors of alcohol abuse spread. He could be brilliant one moment, maddeningly undisciplined the next.

He was knocked down twice in a seven-round loss to Gervonta Davis in April 2023, for example, suffering his first loss as a pro. Then two fights later he knocked Haney down three times, only to have the win ruled no contest when he failed a drug test.

Boxing is littered with world champions whose careers were destroyed by drugs, alcohol or lack of focus and discipline, dating to the early 19th century and bare-knuckle champion Tom Molineaux, who died penniless at age 34 of an alcohol-related illness. More recently drugs cost two-time welterweight champion Aaron Pryor one of his world titles, heavyweight champion Tyson Fury saw his career stalled by cocaine and depression, and Edwin Valero, an undefeated world champion with a violent temper, was arrested for assault, then murder, during an eight-month descent into hell that ended with the boxer dying by suicide in a Venezuelan prison cell in April 2010. He was just 28.

Ryan Garcia, left, is knocked down by Gervonta Davis during their title fight at T-Mobile Arena in Las Vegas in April 2023.

(Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times)

Robles said Garcia, who can’t compete in a sanctioned fight until next spring, may be at a similar fork in the road, with one path leading to redemption, boxing glory and unimaginable riches and the other leading to who knows what. What Garcia does during this forced timeout he earned for bad behavior will go a long way toward defining that path.

“Just depends on what he’s doing with himself,” said Robles, who trained heavyweight world champion Andy Ruiz Jr. and female world champion Mikaela Mayer, among others. “Is he really working on himself? Is he being a better person really? That’s the question. And we won’t know that until he comes back to the ring. I hope he doesn’t end up in a bad place.”

But, the longtime trainer cautioned, “the kid better wake up and realize that that could all be gone and over. Especially if you’re hanging around with the wrong people, the wrong crowd, the wrong circle, you’re going to end up in a very dark place.”

Nobody knows exactly when Garcia’s career began spiraling out of control, but there’s widespread agreement why. If few opponents could give the hard-punching fighter trouble inside the ring, the demons he battled outside the square circle — mental health challenges and alcoholism — have proven far tougher.

“I’ve been struggling with mental health for some years now,” he said recently. “I just try my best to work with my highs and lows at times. That’s just something that I had to go through.

“Sometimes you gotta, you know, take a little pause and try to come back. That’s what I did.”

Garcia was seen drinking in public before the Haney fight — he even drank a beer at the weigh in, where he was 3 ½ pounds overweight — then two months after the fight, a reportedly drunken Garcia was arrested for felony vandalism and hospitalized after causing $15,000 in damages at the Waldorf Astoria Beverly Hills.

When Garcia paid for the damage the hotel declined to pursue the case and Judge James P. Cooper III last month granted a civil compromise, essentially dismissing the charges over the objections of L.A. County Dist. Atty. George Gascón, who said he wanted the boxer held accountable.

A couple of weeks after the hotel episode Celina, Garcia’s wife, posted photos of the damage she says the fighter caused at her Porter Ranch home in another drunken rampage. Both incidents occurred shortly after Garcia said he learned his mother, Lisa, had been diagnosed with breast cancer.

“I was going through a hard time. It was just me having one emotional moment,” said Garcia, who is again living with his wife in Porter Ranch as the couple reportedly tries to save their three-year marriage, though the boxer was publicly linked to two other women in the past nine months and his divorce petition remains open.

In between the two violent incidents, Garcia’s father, the man who sacrificed his own career to launch one for his son, said Ryan stopped speaking to him. So he did interviews and took to social media to urge Ryan to seek therapy for his addiction. His son sent a response via X, claiming — inaccurately — that he had given up drinking.

Ryan Garcia speaks during a news conference in Las Vegas in April 2023.

(Steve Marcus / Associated Press)

Father and son have since reconciled as the boxer slowly and haltingly begins to acknowledge the obvious: his drinking could wipe out everything he’s worked for. His nickname is “King Ry,” but at the moment the king has no crown, having been forced to relinquish the WBC lightweight title he once held.

“I want people to know that I’ve self-reflected and that I’m bettering myself mentally and physically, especially with alcohol,” he said. “I want people to know that I’m going to still be a pain in the ass, but as far as promotion-wise and everything else, I definitely want to be a role model.”

That’s about as close as the likable Garcia gets to a mea culpa during a quick if wide-ranging interview at his lawyer’s home as his driver/bodyguard/escort waits outside behind the tinted windows of a black SUV.

The irony of Garcia largely shrugging off his problems was thick because before his 2023 loss to Davis, who had his own well-chronicled trouble with the law in South Florida, Garcia mocked his opponent for not having a moral compass.

“It’s a gift to me to know what’s right or wrong in life, even in little instances,” he said then, a take that has not aged well in the intervening 18 months. “That’s not something you teach.”

Although Garcia, his heavily tattooed body hidden behind a loose-fitting T-shirt and blue jeans torn at the knees, is surrounded by the wreckage of his career, he remains confident he can put it back together again. And he definitely has a lot of people in his corner.

Golden Boy founder Oscar De La Hoya, who had his own well-publicized legal and substance-abuse issues during a career that saw him win 11 world titles in six weight classes, has been advising Garcia, as has Golden Boy partner Bernard Hopkins, who, as teenager, was convicted of nine felonies and sentenced to 18 years in prison before turning his life around and becoming a multi-time world champion.

“He’s not the first one to go through problems like these. And we’re always going to encourage him,” Golden Boy president Eric Gómez said. “We want the best for him and if anybody can do it, Ryan can. He’s still young.

“If he really focuses on what he does best, which is boxing, he can overcome anything.”

(Another reason Golden Boy remains with the 26-year-old Garcia is financial. If the boxer gets his career back on track, he’s young enough to become one of the best-paid fighters in the sport and the promoter, whose contract with Garcia extends into 2026, will cash in.)

Garcia no longer drinks at home, he says — but that was never really the problem — and concedes the pressure of being in the public eye led him to turn his social media accounts over to other members of his team. (Many of Garcia’s problems, a source close to the boxer said, were caused by Garcia’s own trolling on social media, where he told tall tales to generate attention only to have the lies repeated wildly, causing embarrassment and forcing his camp to walk them back.)

He’s also learned to watch his behavior when he goes out.

“I’ve kind of had to adjust my life to that,” he said. “I can’t do anything without people knowing.

“Everyone’s taking pictures. TMZ’s there. It just gets annoying.”

Ryan Garcia celebrates after defeating Oscar Duarte during a welterweight fight in Texas in December 2023.

(Carmen Mandato / Getty Images)

“People started kind of relating to me. You know how people love the anti hero? He’s a bad dude, but damn, I kind of like this guy.”

— Ryan Garcia

Robles has a different theory. Garcia’s problems didn’t begin with a bottle or a social-media account, he says. Instead it began in early 2022, when the boxer left the camp of Álvarez, the hyper-disciplined Mexican world champion, and Reynoso, his trainer.

“That’s the worst thing he could have done,” Robles said. “What better role model is there than Canelo Álvarez? He’s a true professional, inside and outside the ring. That could be Ryan. But instead he’s somewhere else, doing all the extracurricular activities.”

Garcia said he left because Reynoso didn’t have time for him, an explanation Gómez agrees with. But Reynoso said the boxer made the relationship difficult.

“He’s a very good kid,” Reynoso said in Spanish shortly after the split with Garcia. “But he’s too focused on the cameras and other things. He doesn’t have a real focus on what is boxing.”

Few sports can match boxing for jealousy, backstabbing and general loathsomeness, so not everyone shares Robles’ concern. In fact Garcia’s critics are having a field day, saying the fighter, once known for his hard work and ring IQ, has become lazy and dumb, has no footwork and even less defense.

Now he’s also been linked to mental health and substance-abuse problems, which can be damning in boxing. And when he begins his comeback next year he’ll almost certainly have to step up in weight to compete as a welterweight, a hugely competitive division.

But Garcia, unlike most current boxers, understands the game. He’s been mentored by Floyd Mayweather and long admired Muhammad Ali, two master showmen who taught him fights need attention to draw sponsors and sell pay-per-view subscriptions. And nothing draws attention like controversy, which Garcia can fan through social media accounts that have more than 15 million followers combined.

If Garcia was once boxing’s fair-haired boy, a fighter who, like De La Hoya, rose from humble beginnings to the top of his sport through dedication and hard work, this year’s series of controversies have stamped him as something else.

“I’m the heel,” he said, borrowing a wrestling term used to define villains. “ … People started kind of relating to me. You know how people love the anti-hero? He’s a bad dude, but damn, I kind of like this guy?

“I think I could turn it on for the fight, for the promotion. But as far as my daily life, I definitely need to tone it down.”

Ryan Garcia stands in the ring before the start of his fight against Devin Haney in April. Garcia initially won the fight before testing positive for a banned substance and being stripped of the win.

(Frank Franklin II / Associated Press)

That appears to be Garcia’s road to redemption. Play the bad guy in the boxing ring while struggling, surviving and sacrificing to become the good guy outside it. Make millions by enticing people to root against his anti-hero while writing a comeback story that ends heroically.

Sounds complicated. But Gómez says it would be a bad idea to bet against him.

“He’s just scratched the surface,” Gómez said. “I really feel that he could be the biggest thing in boxing. He just needs to focus on his craft a little bit more.

“He’s got the talent, he’s got the looks. He’s very personable. If he focuses, the sky’s the limit.”

Times researcher Scott Wilson contributed to this article.