Last month, Mariusz Wirga, a Long Beach doctor, saw a break in his packed schedule, grabbed his skis and dashed off to Mt. Baldy to enjoy the fantastic new snow left by a recent storm.

A former ski instructor, he was carving a fine line, lost in the rhythmic pleasure of crisp turns when, out of the corner of his eye, he saw a young snowboarder barreling toward him from above.

Wirga swerved to avoid the imminent collision, caught an edge and slammed to the ground so hard he felt his right arm pop out of the shoulder socket. It stretched as far as the muscles and tendons would allow, then snapped back with bone-shattering force. The pain took his breath away. He slid about 100 feet down the hill knowing he would soon be in an emergency room.

Skiing has always had its risks, but the true number of injuries is difficult to ascertain. Resort employees respond to most injuries, so resorts probably have detailed statistics. But the numbers they share with the public are broad and general. The National Ski Areas Assn., a trade group, acknowledges about 80 catastrophic injuries and deaths per year in the U.S.

A sign at Mammoth Mountain asks skiers and snowboarders to maintain a safe distance from one another.

A Times analysis of a vast state database of hospital visits paints a much bigger picture: In California alone, more than 6,000 skiers and snowboarders visited emergency rooms in 2022 with injuries sustained on the slopes, according to data maintained by the California Department of Health Care Access and Information.

Of those, 193 were hurt so badly they had to be admitted to the hospital for extended treatment.

And the number of recorded injuries is rising at an alarming clip. Ski-related ER visits are up 50% from 2016 through 2022, the state data show. During that same period, the number of skiers and snowboarders remained essentially unchanged in California, according to industry data.

That suggests the slopes at celebrated resorts like Mammoth Mountain in the Eastern Sierra and idyllic Lake Tahoe destinations such as Heavenly, Palisades Tahoe and Northstar have grown more dangerous.

Public relations executives at Mammoth Mountain and top Tahoe resorts declined to answer questions about the number and types of injuries their customers sustain. And The Times’ efforts to talk with their ski patrollers, who usually are the first responders to accidents on the slopes, were rebuffed.

But former ski patrollers, emergency medical technicians and hospital staff in mountain towns confirmed they are seeing a rise in accidents — and place the blame on a few primary factors.

One is a growing recklessness on the slopes that seems to have emerged post-pandemic, behavior often exacerbated by people ingesting pot gummies, magic mushrooms or copious amounts of alcohol before hitting the slopes.

Another major factor: Skiers so focused on taking selfies and shooting video for their social media feeds that they are oblivious to what’s happening around them.

“Oh, it’s noticeably getting worse,” said Jessica DeMartin-Miller, an ER nurse at Mammoth Hospital. “People are just checked out. They have their headphones in, their video cameras going, like their experience is the most important experience and that’s all that matters.”

A snowboarder scrapes the top edge of a halfpipe at Mammoth Mountain.

DeMartin-Miller used to be a search-and-rescue nurse in Yosemite National Park, and in her spare time she manages a business leading private clients on mountaineering adventures. She is no stranger to well-managed risk. But the crowds hitting the slopes post-pandemic are showing a level of irresponsibility and reckless abandon that makes her nervous.

“We get people in the ER with serious injuries who say they just had ‘a couple of beers,’ but they reek of alcohol,” she said. Or she’ll ask if they’ve been smoking pot and they’ll insist they haven’t, almost indignantly. But when she asks if they’ve eaten gummies or mushrooms: “They’re like, ‘Oh, yeah, sure.’ ”

And it’s not just the number of injuries that seems to be increasing. So is the severity.

Dr. Kyle Howell, a physician in Mammoth Hospital’s ER, says ski injuries are increasing in number and severity. Among the causes he cites: on-slope collisions and the growing popularity of Olympic-caliber terrain parks.

On a busy Friday shift in early March, Dr. Kyle Howell said he saw four patients rushed from the slopes to Mammoth Hospital’s ER with punctured lungs, two with air in their chest cavities around their hearts. And he spent hours “fixing the face” of a kid who had smashed into a tree.

Howell said he doesn’t normally have to juggle that many serious cases at once. But the injuries were pretty familiar. At least two of the patients with punctured lungs had not fallen on their own. They had been hit from behind by skiers or snowboarders careening out of control. The impact had broken their ribs and burst their lungs.

“Personally, that’s my biggest fear when I’m skiing,” said Howell, who has worked at the hospital more than 20 years.

He doesn’t push himself so hard on the slopes now that he worries much about falling, but getting hit — especially by someone out of control — haunts him and many other locals.

“It seems like there are a lot more collisions than there used to be. That’s what we all worry about,” Howell said.

Dr. Kyle Howell shows a diagnostic image of a skier’s broken wrist that has been secured with hardware.

Also playing a role in the severity of the injuries Howell treats is the rapid expansion of terrain parks equipped with enormous ramps and giant halfpipes designed for the kind of soaring acrobatics you see in the Olympics.

Years ago, when kids built little ramps at the side of a ski run, ski patrollers would demolish them with shovels and threaten to confiscate the kids’ lift tickets.

These days, resorts build the ramps — massive ones — for their customers. They’re a big draw and feature heavily in marketing materials. The hype tempts inexperienced people to go faster, bigger and higher, with predictable results.

“It’s not uncommon for me to treat several patients on a given day who have suffered what amount to 40-foot falls when they overshoot the landing on big jumps,” Howell said. “These are just massive, massive falls, and they cause the kinds of injuries we only used to see in professional athletes.”

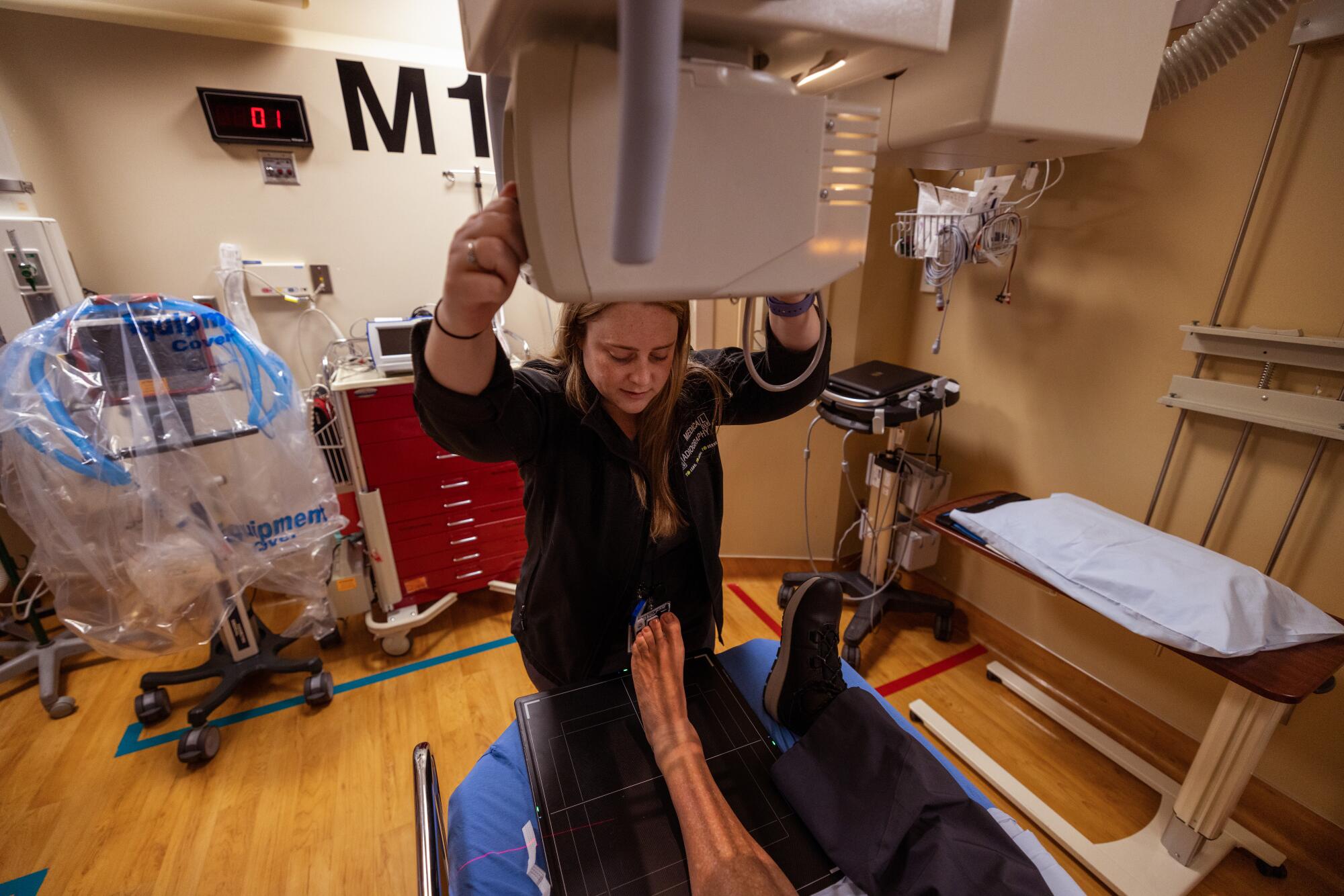

Mammoth Hospital technologist Kylie Hansen performs a diagnostic scan on a skier’s injured ankle.

Social media delights in the mayhem and rewards the people who film it with seemingly endless attention. An Instagram account called Kookslams, which specializes in clips of surfers and skiers going big and biting it hard, has 2.4 million followers.

One video that went viral this month shows a skier launching off an impressive ramp and going so high he slams into a moving chairlift in midair. It’s simultaneously cringe-inducing and hilarious, and seemingly everyone interviewed for this story had seen it. Several cited it as a prime example of social media’s odd ability to both document and inspire reckless behavior.

Another clip almost everyone interviewed had seen shows a 16-year-old girl falling 30 feet from a ski lift at Mammoth last month. It was filmed from multiple angles, and the clips got more than a million views on YouTube.

Part of the draw was the suspense: The teenager dangled for what felt like an eternity as resort employees and volunteers scrambled to get beneath her with a net. It looked as if they had things under control until the girl let go and mostly missed the net, slamming to the ground.

She survived, but not without injury. And what happened to her is not an isolated incident.

The number of emergency room visits for accidents involving ski lifts more than tripled — from 16 to 53 — between 2016 and 2022, according to the state hospitalization data.

A skier takes a fall on the slopes at Mammoth Mountain.

On a recent Friday morning, the Broadway chairlift at Mammoth, which serves mostly intermediate terrain just above the main lodge, was busy with locals getting in a few last runs before the big weekend crowds — and their chaos — arrived.

All but one had an emergency room story to tell.

Rob Connor said he had been knocked out twice by snowboarders who hit him from behind. The last time, he said, “I heard a whoosh, and the next thing I knew I was seeing stars.”

When he regained his senses, Connor said, he saw the snowboarder who hit him waiting a bit farther down the hill, staring back at him. He appeared to be making sure Connor wasn’t dead before speeding off without a word.

Another local skier confessed that he had been the one to cause a collision with a snowboarder. He had failed to look uphill to make sure nobody was coming before crossing where two trails intersected. The collision left him with a separated shoulder and the snowboarder with an injured knee, he said.

The only lift companion who did not have an injury tale to share confided, just before he got off at the top, that his wife worked for the resort and that he wouldn’t tell the reporter even if he had been in an accident.

“The mountain doesn’t like to talk about this stuff,” he said with a laugh.

In an emailed response to questions, Michael Reitzell, president of Ski California, an industry trade group, said that skiing is an inherently risky sport and both the resort operators and skiers know that injuries are going to happen.

He said that is why the industry has worked hard to educate skiers about safety practices, such as keeping a safe distance from others on the hill.

“Twenty years ago, most people didn’t wear helmets,” Reitzell said. “The industry started educating around it, and now almost everyone wears one.”

Posted signs at Mammoth Mountain warn users to slow down near trail junctions.

Skiing and partying have always gone hand in hand; it’s a sport that attracts hedonists and thrill-seekers. But before the pandemic, most of the debauchery was saved for afterward in the hot tub.

That seems to be changing. To adapt, DeMartin-Miller said she and her colleagues have a hack to figure out if they’re about to get busy: They check the webcams on mammothmountain.com to see if the outdoor bars are filling up while the lifts are still running.

Hard partying might be fine on a fishing trip or a golf outing, said Caitlin Crunk, Mammoth Hospital’s chief nursing officer. But skiing is a sport that requires fine motor skills and reasonable inhibition. She can’t understand why anybody would want to do that drunk.

“You’re like a 30-mile-per-hour weapon out there, bombing down the hill with, essentially, swords on your feet,” Crunk said. “That’s just a recipe for disaster.”

Aside from legs broken just above the top of the ski or snowboard boot — known as “tib fibs” in ER parlance — more serious life-threatening injuries are also far too common, she said.

People fall on ski poles and rupture their spleens. They fall wrong on the phones in their pockets and lacerate their livers. But the worst are the head injuries sustained by skiers who still refuse to wear helmets.

“That’s our big push, asking people to wear helmets,” Crunk said. “We can fix just about everything else. But if you hit your head, there’s not a lot we can do for you.”

Crunk said she’s stunned by the number of complete beginners who go way beyond their limits in search of the perfect social media post. A classic mistake is riding the gondola to the 11,053-foot summit to get a selfie with the iconic signpost that marks the top, only to discover there is no easy way down. Those people often wind up hurtling out of control down harrowingly steep expert trails.

“They’re just missiles up there,” Crunk said, the disbelief obvious in her voice.

Mammoth Hospital ER nurse Kory Ferguson, right, tends to a skier with an ankle injury.

Like many Mammoth natives who grew up avid skiers, Crunk said she mostly avoids the mountain now, especially on weekends. When she does go, it’s to make sure nobody plows into her young son.

When Wirga, the Long Beach doctor, got to the ER after his accident, X-rays confirmed what he already suspected. He had suffered a serious fracture and dislocation of his shoulder. He endured surgery and has been warned to avoid strenuous sports for a year.

He said the kid who caused the accident was kind and clearly worried about him. He hung around asking, repeatedly, if Wirga was OK. “I told him I understand, [stuff] happens, but I was definitely not OK,” Wirga said.

It seemed he wanted reassurance that his reckless behavior had no real-world consequences.

“I didn’t give him that,” Wirga said. “I didn’t give him that absolution.”